December, 2017

☙☯ Wilson, Wyoming ❧☯

BY late 2017 decrepit knees had reduced me to the status of a prisoner in solitary confinement: one hour of daily exercise (usually skiing). Pushing it would leave me crippled for three. Drugs and alcohol didn't help. Around Christmas, a big book entitled “Walking Distance” appeared on the coffee table. It was was a setup. The first walk was the “Alta Via 1”. My wife had seen an article in Outside Magazine about the AV1 and bought the book. When I opened it, she struck like a stinger missile: “We have to do this!” “No way...” I replied. “Maybe it’s time you got those knees fixed.” she suggested. I had been on the orthopedic merry-go-round so often that I was the clinic's poster child. Unpleasant thoughts of past surgeries faded in the face of the astounding beauty of the images and memories of via ferratas from a turn-of-the-century visit to Cortina. Early the following spring both knees were swapped for new. On the last day of August the group of friends my wife had collected for our adventure were standing at the doors of the Park Hotel Bellevue in Dobbiaco Italy, certain that the company behind our adventure had put us in the wrong place for our first night. It was ritzy, with four gleaming stars above the entrance and a smiling guy waiting to take our bags. We settled into our new digs, figured out the Euro windows, plumbing and power, then headed out to explore.

Dobbiaco it. / Toblach gr. is one of a string of pretty villages in the multilingual Val Pusteria nestled between Austria and the northern slopes of the Dolomites. It’s main claim to fame is that the composer Gustav Mahler visited for better "air", plentiful sunshine and happy people. An enduringly popular festival takes place each summer, celebrating the composer’s music, Austrian roots and his stature as a sort of home-town boy. Once part of Austria, the valley was ceded to Italy after WWI, but like much of South Tyrol, it is now an autonomous region and retains its Germanic character. It is said that in Val Pusteria, even the cows smile...

The village center is home to the ubiquitous Catholic church and a busy bus terminal where the massive influx of tourists are sorted, boarded and hauled off in one direction to marvel at the Tre Cima Lavaredo and in the other to marvel at Lago de Braies . It was from this lake that we departed with our hearts full of sunshine and a sky full of rain. The two kilometer walk along the lakeshore would be the last level ground of the trip. Once we had made our way through the gauntlet of tourists and cows with lethal looking horns and inscrutable stares, we began the 1,000 meter climb - also the longest continuous ascent of the walk - to Forcella Sora Forno. Forno means “oven” or "furnace" and refers to an aptly-named south-facing basin of dark rock near the forcella that can often be windless and very hot. For some, it marks the end of their Alta Via I. For us, the Forno was saturated with rain so we chuckled about its dire reputation while trying to keep our boot tops above water on the flooded trail as we made our way to the pass. There, we were treated to a face full of wind-driven mist. Even Madonna seemed a bit resigned to facing windward.

The weather had tempered our expectations, but we remained idiotically happy with our first day’s accomplishments. Though our destination lay only an easy hour away, the 400 meter side trip to the summit of the now mostly obscured and sopping Croda del Becco with its exposed sloping slabs had lost the last of its appeal. We all agreed that Italy had punished us enough for one day and contented ourselves with wandering through the rolling high meadows and flocks of sheep to Üćia Sennes.

We were welcomed there and taken to our small suite of rooms. We would come to discover that the agency that had booked our walk had developed partnerships with the rifugios and hotels along the route. We were introduced to our rooms - replete with cookies, chocolates and shower tokens - and shown to our table in the dining room. We would, for the duration of the two week walk, come to be known as “Il Gruppo Olson”.

From the look

of the ARPA report posted in the dining room, we could expect another day of the same: broken to overcast clouds with rain and cool temperatures. No problem, we assured each other as we gathered for the day two group photo. We were warm, dry and well-fed, if not a bit hung-over as we headed down the two-track in the drizzle, blissfully unaware that over the course of the day, we would lose 600 meters of elevation descending to Üćia Perudu, then regain it to reach Üćia Lavarella. The poor weather had filled every bed, so there were scores of multilingual, multinational walkers in contrast to yesterday’s marked solitude. The leader of one guided group was a flashy fellow with fluorescent orange boots who leap-frogged us through the day. The staff seemed to know him and referred to him among themselves as “gallo”, which I later found meant rooster. As is common with trips where the same folks seem to find themselves saying hello at each breakfast and dinner, some ephemeral friendships were formed. Ours happened to be with three fellows from Salt Lake City who we first met waiting at the Venice bus terminal, then on each of the first three days day along the walk. We knew them as Doug, Dan and Dave, but never well enough to remember which D was who’s …

After 600 meters of steady climbing, it was a weary and somewhat subdued group that arrived at Üćia Lavarella. The sun had chased away most of the clouds and we enjoyed the last few hours of the day drinking beer, nibbling on local chamois sausage and cheese, and watching the few small snow patches from the previous two day’s weather slowly disappear. At 2000 meters, Üćia Lavarella lies midway between the encircling valleys and highest summits of the Dolomites. At 47 deg. North, the same latitude as Montreal, Helena Montana and UlaanBaatar, Mongolia - not exactly locations we associate with a place in sunny Italy.

Chapel at Ǖćia Lavarella

At breakfast I again watched as now three members of our party had taken to secreting food away for their lunches, though there was a sign politely discouraging this petty theft and lunches were no more than pocket change for us. We seemed not only compelled to identify ourselves through this seemingly singularly Trumpish act of self-entitlement, but to remain steadfastly immune from shame and ignorant of the economic effect of this cumulative pilfering over the course of the season. For the second day, I left an additional €20 when I settled for the group, not so much for the food as for the tolerance the staff practiced while hosting us.

We departed under wall-to-wall blue skies and climbed into “Le Gran Plan” a nearly level valley that we would follow for several kilometers before dealing with the serious elevation changes for the day. Assured by Gallo’s shouts of “Lagazuoi!”, map checks were unneccessary and we made good time. As in most other European countries, trail signs display times rather than distances. I have always entertained a conspiracy theory of a rivalry of who’s citizens are the most fit and thus post the shortest times on the signs. According to my theory, the Swiss excel at posting times that inspire utter hopelesness. For me this is entirely rhetorical since, regardless of country, I have never been able to meet any of them. Confounding to many Americans, times do provide some additional hints of general difficulty. This is a nifty bit of information that is otherwise hard to gauge if you have only simple distance and rudimentary map skills.

By early afternoon we had finished our casual stroll up Le Gran Plan and arrived at the junction of trail 20B. This trail leads first up to Forcella di Lech, then down and along the shoulder of Croda Scotini, and finally up the Mordor-like northern slopes of Monte de Lagazuoi to its namesake rifugio perched on the ridge overlooking Passo Falzarego. We searched the sparse pines for toilet spots, took some pictures of the stunning views from this broad pass that had opened to the south, ate some lunch and chatted with the three Ds. Given the root of the group's bond - that of becoming friends and fellow mountain addicts in the Tetons - we were hyper-sensitive to what the Dolomites were now revealing: the unique panorama of rock and time, and similarities and differences with peaks of home. It was getting better with each step. 20B is a shortcut that avoids the 5 km, 500 meter down-then-up traverse of Piza di Lech. It is the path of least resistance but not the path of least consequence, as is often the case with mountain shortcuts. It is a narrow path traversing a steep series of hillsides, in places too narrow and steep to pass. Not steep enough for a cable but steep enough to fall off. It would come to define the character of walking among these peaks.

Ninety minutes and 400 meters later we were at the forcella. The long summit ridge of Monte de Laguzuoi filled the skyline, hiding the stupendous views southward. The rifugio looked to be at about our elevation - actually 300 meters higher - and about as far away as the moon. Unfriendly-looking clouds were building to the south. Most of our fellow adventurers, including Gallo's group, were getting their second wind and quietly steeling themselves for round two. For some, three consecutive days of elevation was beginning to show. But they were all younstgers, so we encouraged them to descend first and brought up the rear, following them down the switchbacks filled with loose rocks and reinforced with logs and rebar. By the time we had finished the descent, it had grown cold and a few wet snowflakes were beginning to stick. There was a little lightning suggesting that this might be a short-lived thunderstorm, but those hopes were slowly extinguished as the snow increased and we shuffled the last two hours through the wind and fog to the rifugio.

We told the manager that we were likely the last to arrive and claimed the remaining, least desirable of the 120 bunks in the dormitories - those on top, closest to the door and at the mercy of the automatic lights illuminating the locker/shower/toilet facilities down the hall. In the dining room however, our table hinted at a magnificent view to the Marmolada, but there would only be a brief glimpse of it, just as the sun set. Laguzuoi is a major, year-round activity center, joined at the hip with its companion tramway 600 meters above Passo Falzarego . There is Cortina d'Ampezzo to the east; Alta Badia to the west; and the valley directly south, in the path of the Alta Via 1, bounded on its left by the masses of the Pelmo and Civetta and on the right by the groups of the Sella and Marmolada. At Lagazuoi you can ski, hike, take pictures, explore history, climb via ferratas - and some serious mountains - buy cool italian souveniers, or just sun yourself to toast on the deck with a world class view.

There were a few pockets of mist on the Tofane. Elsewhere the morning's 360° horizon was cloudless, finally revealing - insert your favorite superlative here - array of peaks, towers, faces and spires. In the Dolomites the forces of nature have conspired to cleverly combine height and distance, resulting in a landscape that from Lagazuoi, is both staggering and sublime. The peaks are arranged in almost textbook groups, separated by valleys in perfect proportion, and interconnected with an impressively engineered system of roads, lifts and paths. Nothing is very far away so the area is not only a day-hiker's paradise for the shuffler and trail-runner alike, but a thru-hikers dream as well. If gnawing on a Nature Valley® and swatting bugs best describes your backcountry lunch, have it instead at a rifugio and never look at another granola bar the same. Knock yourself out and remember that you probably still have somewhere to be.

Three members of the group had all worked together as Park Naturalists, a unique kind of hippy. They share a genetic predisposition known as "interpretive tendencies", a compulsion to teach sometimes unteachable people cool things and remain optomistic while doing it. I had seen Lagazuoi and its sad war machinery before, so I left them to their curiosity and ambled down to the pass. It was the first of the four roads we would cross along the way. Though it was only 11 am, there were others at the restaurant drinking beer. Feeling under pressure to fit in, I asked for one and a panini, found a seat in the shade, and watched my group make their way from one ruin and flower patch to the next. From their progress, it appeared I might have to pace myself with the beer, then realized that, since we were headed to Cortina and our rest day, the only tricky move remaining for me was to get on the bus. "Un altro per favore ..."

Alpine Exploratory, our booking company had selected the Ambra Cortina Luxury & Fashion Hotel for our day in Cortina, taking us from a room filled with flashing lights, snoring and flatulence to one of silk sheets and cold prosecco. My wife and I scored the "Sean Connery" room. The person at the desk corrected our assumption of a James Bond connection. "No, Mr. Connery didn't make a Bond Film in Cortina. That was Roger Moore. Signore Connery is a friend of the hotel". That settled, we took to the streets. Contrary to a popular meme, Cortina d'Ampezzo is not the Jackson Hole of Italy and, so far as I can tell, has no interest in being considered so. "The Curtain of Ampezzo" has been won, lost, annexed, ceded, traded and gifted going back at least to the Etruscans. Folks were burying their dead in the surrounding mountains some 5000 years before that. That is history. It remained a sort of chic-dirtbag secret ski spot until being propelled into world-class resort status as the site of the 1956 Winter Opympics (and the upcoming 2026 Winter Games). It lies in the upper reaches of Valle del Boite, nestled between the Tofane, Cristallo and Sorapis groups. A cork dropped into the Torrente Boite will eventually find its way to the Adriatic Sea via the Fiume Piave on the eastern flanks of the Dolomites. A walk along the streets early in the morning reveals a little village that seems momentarily innocent and untouched by the glitz and glamour.

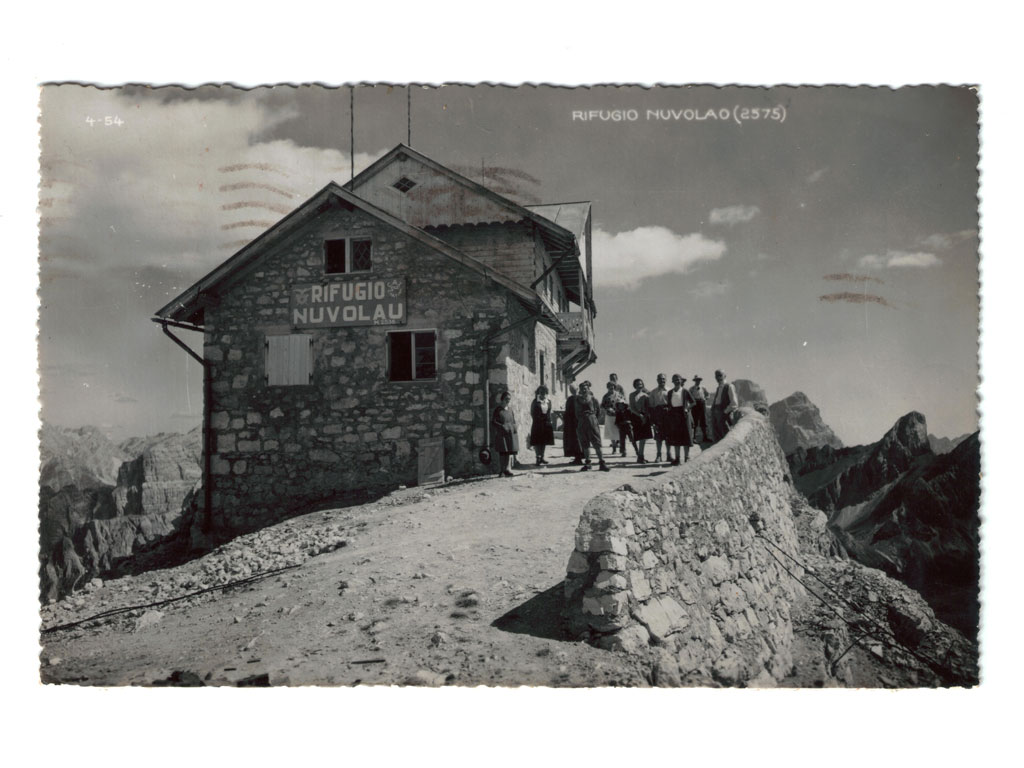

"Rifugio Nuvolau"

Acqua non Potabile... Partway through dinner, bad water from an incorerctly assembled water filter used the night before had begun to sicken two of the group, and by morning, Lagazuoi's Revenge had incapacitated them. With every bed still filling along the walk, I called AE to forwarn them of our possible delay only to be assured that it would be taken care of. My wife's insistence on using an agency for this first hut-to-hut walk in a foreign country once again proved to be the best idea we had. The abdominal scourge was short-lived and by the following morning we assembled for the five-fingers up photo op and boarded the bus to rejoin our walk to the day's destination, Rifugio Nuvolau. Even though we took the lift to Rifugio Scoiatolli and had a second breakfast there, the remaining pull to Nuvolau was slow. In various states of health, we arrived in rain that turned to snow and waited, eating brats and drinking beer until 2pm when the door was opened and a rainbow appeared seemingly on cue. We could now gaze back at Lagazuoi, from where two days before, we had gazed at Nuvolau. What our funky, rustic home for the night lacked in amenities, it made up for with the dramatic head on views that the roadmap perspective from the loftier Lagazuoi could not capture. Nuvolau is the oldest rifugio in the Dolomites and, just out of artillery range, served as a forward observation post for the Italian forces during the "Great War". It escaped destruction from aerial bombardment only because it was obscured by the very clouds for which it was named, however the brief, romantic version of the story related by the fellow cooking the brats was that, out of love for the tiny perch that he had visited often in his youth, the pilot deliberately missed his target, destroying the bagno instead.

The rifugio's little supply tram was broken so breakfast, like last night's dinner, was quick, simple, and largely ceremonial. Most walkers going south from Nuvolau follow the popular Ferrata Gusela to Passo Giau and on. Lacking via ferrata kits, the disappointing weather simply meant we would return the way we had come to Rifugio Scoiatolli then take the much longer path through the Crépe Die Ronde and around the east flank of Monte Nuvolau to reach the road - and do so in the rain. From there our route stretched on for another 9km over a series of barren, windswept passes and high grasslands to Rifugio Città di Fiume. There were things to see as we walked the high meadows from pass to pass but they remained hidden until reaching Forcella Ambrizzola from where Cortina lay visible in the valley below through a rip in the clouds. On the ascent to this pass, a softball-sized rock whizzed by my head close enough to audibly caress the hood of my jacket. Had it struck me, it would have killed me outright. With two immense bounces off the steep turf, it exploded in the boulder field below. A hundred meters or so above, there was a group of chamoix watching us, and I had a flashback of eating chamoix sausage at Üćia Lavarella and being targeted by a vengeful relative. Karma ...?

Monte Pelmo is a 3000 + meter solitary monolith straddling the Boite and Zoldo valleys. Its position of prominence again hints at a conspiracy of grand design. It comes complete with a glacier that must be negotiated to reach a number of spectacular alpine routes up the near vertical series of steps, ledges and seasonal ice gullies leading to the summit. Rifugio Città di Fiume lies directly under this N face, some 1200 meters below the summit. Our march to it ended just in time to remove our boots, drop our packs and get the last serving of dinner. Later, reading the rifugio logbooks, I discovered that far from being left to bask in the history of its classic routes, Monte Pelmo, particularly its northern aspect has received renewed attention from those looking for serious mixed climbing.

The intermittent sounds of rockfall from the face above with its fresh coat of snow and ice encouraged a snappy pace as we crossed the vast scree fields beneath it. This otherwise straightforward traverse was complicated by several washouts cutting through the slope, one of which was very recent and required crossing one at a time due to the loose rocks and patches of rubble. Today would be a double-double, as we would pass under the north faces of both Monte Pelmo and Civetta. We eventually left the scree for a forested trail that deposited us at the rifugio at Passo Staulanza for coffee and a pastry, and we joked again about our "impeccable" timing - actually anytime is a good time to visit a cafe in this country. We crossed the road between groups of motorcycles and resumed our forest descent only to cross it once again 220 meters lower at Palafavera - more motorcycles - from where we walked along a two-track through beeches, then small pines to the base of Civetta. The road became a walled path leading steeply to Forcella Coldai and views to the west of Alleghe, its pretty lake, and the valley of the Torrente Cordévole with its headwaters now far upstream at Passo Falzarego. While Civetta is not as high as Monte Pelmo, it is a much more complex massif with its intricate collection of ridges, faces, couloirs and towers. On the official maps it is referred to simply as Civetta . It is a full five kilometer walk along the conveniently situated shelf of the Val Civetta until a break in the ramparts is reached. Along this walk some of the greatest alpine climbing routes in Italy can be studied in detail on the walls that seem almost at arm's length. I dallied along this stretch, reading plaques and memorials of great climbs and climbers and their triumphs and tragedies. This put me an hour behind the group, giving them an opportunity to get lost and me one to find them just below Rifugio Tissi. Being now almost as far from the AV1 as we could possibly wander, it seemed logical to have lunch. It was good, and the view was even better. Except for some base jumpers and climbers in the sun near Torre Venezia, the rest of our second consecutive, long day to Rifugio Vazzoler was warm, sunny and uneventful, ending with cold beer on the patio.

I met my future wife during our first season as National Park Service employees. She was an interpreter, filled with determination and considerable knowledge of the natural world. I was a ranger in a mountain park, filled with summit aspirations and testosterone. I quickly realized I would not be able to fake intelligent conversation with this woman, so I listened carefully when she spoke of the plants, animals and natural processes of the park. Paying attention paid off. Some 48 years later, here we were, wandering through the delightful "Giardini Alpino" of Rifugio Vazzoler. There were a few late season bloomers among the mostly dormant residents, and it was not yet time for the larches to turn so we entertained ourself with a bit of taxonomy, discovering that many of these plants had relatives in our Wyoming back yard. Rifugio Vazzoler is a place for climbers, a simple, utilitarian Italian Alpine Club stopover on the way to or from a summit. Some who visit this place voice disappointment with its lack of glitz, space and hot water. They are unable to get past the warm wine or to relate to the person across the table who may well have spent the past two days in a dripping tent and finds this roof over his head to be a veritable palace. To me, these seem to be the misplaced expectations of misplaced people.

We were beginning to think of our booking agency more as handlers and trainers, now having laid out a third long day for us along the base of the Moizza, a twin-summited southern extension of Civetta and nearly as massive. We were to go all the way to the final road at Passo Duran and were beginning to wonder if, somehow someone had misrepresented us to the agency as a group of iron-eating, fire-breathing, mega-hiking youngsters. For no other reason than being in front, the circumstantial evidence pointed at me rather than my wife, the true culprit, who was grumbling as much as the others. I took to simply walking and waving a peace sign (or fraction thereof) from each hand for every groan I heard. Though only about 100 meters difference in elevation, the path between Vazzoler and our high point Rifugio Bruto Carestiato accumulated a lot of up and down. We grunted up the last hill in the hot sun to find ourselves surrounded by day-trippers from nearby Passo Duran. The sounds of unhappy children and odor of cigarette smoke hung in the motionless air around the tables so we made quick work of lunch and headed down the long incline to the pass, with "Buongiornos" to those who had chosen to take on the hill in the heat.

Perhaps this shows my age, but I have come to classify amenities via a sliding, location-dependent monetary scale: beer is worth 5 euros; a bed: 30; a shower: 10; food: a lot; and not having to set up camp: priceless. Although the parking lot was full, the rifugio was nearly deserted. We had our own rooms, showers and toilets. Freshly scrubbed and smelling of gardenias, we flopped into the deck chairs. The beer appeared almost magically. Could life be better? Yes it could. Our bags, last seen in Cortina, arrived with fresh clothes and a bit of good bourbon. We could even dress for dinner...

Pale San Martino

"It's only fair to warn you that today will be longer than yesterday." my wife said at our morning pep-talk, sounding a bit like an insurance agent explaining an exclusion to an unwary policy-holder. No one cared. San Sebastiano had been the best stop on the walk. We had slept and eaten well, and everyone, including those with new knees and new hips was getting in pretty good condition. The packs were going on without a grunt and everyone had their sunglasses. We even smelled good. We were set. Though the mountain groups through which we would pass today were lower in elevation, they became more wild with each kilometer. Soon, we found ourselves a long way from anywhere and even the valley-bottoms seemed uninhabited. Eventually our path took us past cow sheds to a high pass, Forcella del Moschesin. To the northwest, at the base of the huge Val Balanzola, lay Forno di Zoldo. A few years later, after bailing from the Alta Via 3, I would take a terrifying bus ride from there to Longarone along the walls of the gorge carved by Torrente Maè, but that is another story. To the west lay unseen Agordo in its own vast valley. Ahead was Cima de Zita with its passage to our destination, still a full 500 meters above. The path to our high point was stealthily indirect, at times going in quite the opposite direction. It was all quite logical in the end and after a skimpy, exposed ridge, we reached the forcella and our high point. It rained briefly. The path down to Pian di Fontana descended a steep grassy slope punctuated by rock fins and cliff bands, now wet from the untimely shower. Here and there short cables showed the way through an intricate series of ledges and gullies. Eventually the rocks disappeared and the path, descending the now exclusively grassy slope to the rifugio below, became insanely steep. I gave my short lecture about poles not being a substitute for balance. On the last switchback, one of us slipped and took a shortcut into the mud at the bottom of the slope. She did, however, stick the landing, drawing applause from those assembled below, apparently gathered in anticipation of this occasional spectacle.

I could not translate "Pian de Fontana" into anything other than "little spring". "Little" does however fit Pian de Fontana, an extremely cosy patch of real estate perched above the Val die Ross. Here there is a small rifugio, a cowshed with bunks, a tiny utility building and the terminus of a supply tram. A small mound above has been leveled into a helipad. One of the employees laughed when I asked her if the helicopter was for supplies or for people who had fallen down the hill getting there. Since racing to get a good bunk was not our style, we were pleasantly surprised to find lower bunks reserved for our party but not surprised to find they had been poached. I climbed to a topside bunk with my legs hanging over the edge. An Australian fellow, a member of a party we had been leapfrogging since Nuvolau, looked at the fat, pink scars on my knees. "Fresh pair?" "Yes, 5 months". "Hurt?" "A bit." "Well mate, take my bunk." "OK, thanks mate." That was easy.

Like Nuvolau, Pian de Fontana was a spartan operation and its supply tram was disabled. Apparently something was missing, for there was a small group gathered at the bar, complaining loudly to the laughing girl. They had her surrounded and dismissed anyone who approached with a glower. What could be so important as to transcend a request for beer? Certainly not anger management. With curses, the group shouldered their packs and departed toward Forcella La Varéta to the south. The relief was palpable, but everyone seemed subdued from this unpleasant interlude. As if to dispel the gloom, the aussie yelled, "Drink up!". We queued up, expressing condolences to the teary girl, and ordering beer to comply with the command. It was time for dinner. Everyone was happy. Someone played a guitar a bit and sang, and after a while, the party moved outdoors. The sun was setting on some distant peaks far to the east - names and heights yet to discover - in journeys yet to make. I went inside and asked about the grappa...

This final day of the AV1 was different. Many of us were saying goodbye to our last rifugio and by most accounts, leaving the mountains behind. Instead of a rifugio, destinations would be far away places: Salt Lake City, or Sydney, or Chicago. Some were returning to work and a couple had brought theirs with them. Most were ordinary walkers but some were carrying kits and helmets for via ferratas on La Schiara, the last big peak along the route. A few had set out up the hill in the other direction. There would be one short steep climb, then it was all downhill for some 1600 meters to the bus and Belluno. Following the climb to Forcella La Varéta, our high point, there was a stretch of nearly a kilometer across another extremely steep hillside that fell away to a series of cliffs, in all some 300 meters. This innocuous traverse was the scene of several tragedies that I had read about at the rifugio the night before. People had become too casual with the terrain, slipped and, unable to stop their fall, tumbled to their deaths over the cliffs below. I thought about yesterday's mishap and gave the group a pep-talk: stop to look at the flowers, stop to take a picture, and stop to look around - otherwise, pay attention. I was relieved when we reached the end of the traverse. It marked the end of my leadership responsibility and 9 days of collecting strays. We agreed to meet at the bus stop at one pm then set off at our individual paces. By 2, we were on the bus. After 10 days of walking, 80 kph seemed fast - 110, insane. An hour later we were in our rooms, trying to figure out the air conditioning. Suddenly our months of planning and our days of walking were ending with an hour of bittersweet celebration in this fantastic country. It was then that I resolved to walk the AV2 the following summer, a decision that would take me on a remarkable journey filled with beautiful places, wonderful people and priceless friendships.

Innsbruck, Venice and Milan are convenient airports, and from them, trains and buses will get you to the Val Pusteria and the traditional northern starts for Alta Vias 1 through 5. If traveling by train, remember to validate your paper ticket before boarding regional trains. English is widely spoken (but not everywhere) and a little Italian, even if mangled, usually gets a smile. Using a booking agency for your first trip can provide start-to-finish simplicity and save you from worrying about details you don't know you should be worried about. Alternatively, it is easy to make your own arrangements. Most hotels and rifugios have an online presence and will take your credit card or require a small deposit via bank transfer or PayPal. Some rifugios, simply because of location, have no wifi or cell service, so a little cash is neccessary. Most will hold your bed for you, so if possible, make the effort to let them know if you're not going to show up so the bed doesn't go unused.

Italy's Alta Vias have become tremendously popular, to the extent of falling victim to cyber-trivialization and pay-per-click internet influence sites. The AV1 receives the most hype. Some people have the time of their lives and some are miserable. Yes, you are in Italy, surrounded by romance and beauty, but you are also in some serious mountains, so adjusting your expectations might be your path to happiness. There is nothing confusing about this. The AV1 is one of the longest, with a lot of vertical differential so it is helpful to know the difference between feet and meters. There are places where you can fall off. There are places where cell phones do not work. Whether you book or travel on your own, expect some frustration with services. These are rifugios, not 4-star hotels, and the folks making you happy have been doing it all summer, sometimes just for the fun of it. Don't pilfer food. If you are reasonably competent and find yourself comfortable with your own company, the Alta Vias are great for solo walking. Some pass through very high and wild country, but I have rarely found myself alone for long. Storms, sometimes extremely vicious, are almost certain in August.

You can pack light, in some cases ridiculously light. I prefer sturdy boots and find gaiters and a short-handled umbrella handy. A sleeping sack is required (and often available to purchase) in most rifugios. You may find trekking poles useful. A via ferrata kit and helmet offer both flexibility and safety, depending on your aspirations, inclinations, and destinations. In recent years, winters have become warmer and drier, and water harder to find. Traditional sources, even those referenced in recent write-ups may have disappeared, so make local inquiries. Paper maps and a compass are good to have if you know how to use them.

"Adults are always asking children what they want to be when they grow up because they’re looking for ideas."

- Paula Poundstone -

![]() will do just what it says and take you down another rabbit hole.

will do just what it says and take you down another rabbit hole.

;

;