1 August, 2019

☙ Bressanone ❧

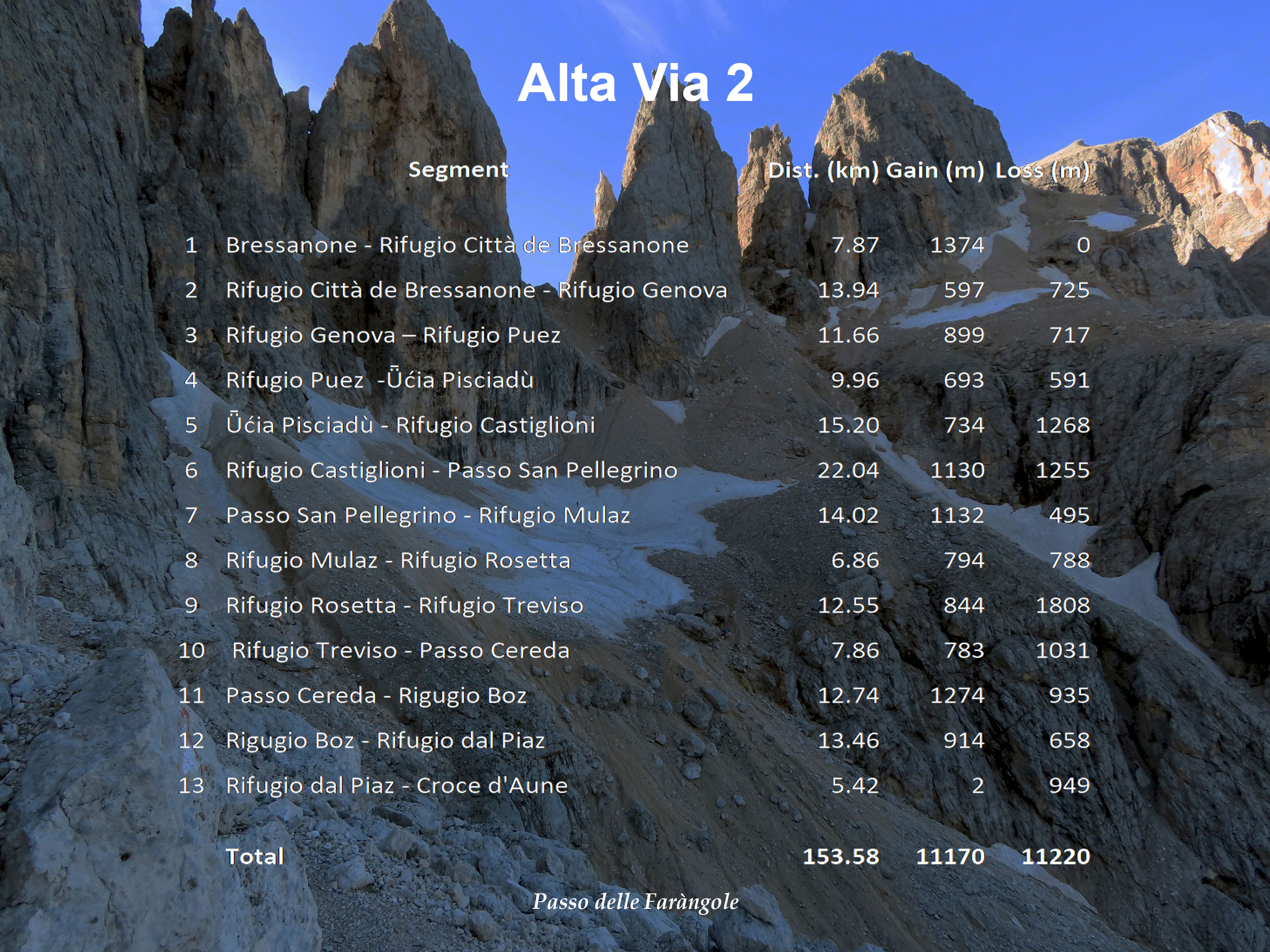

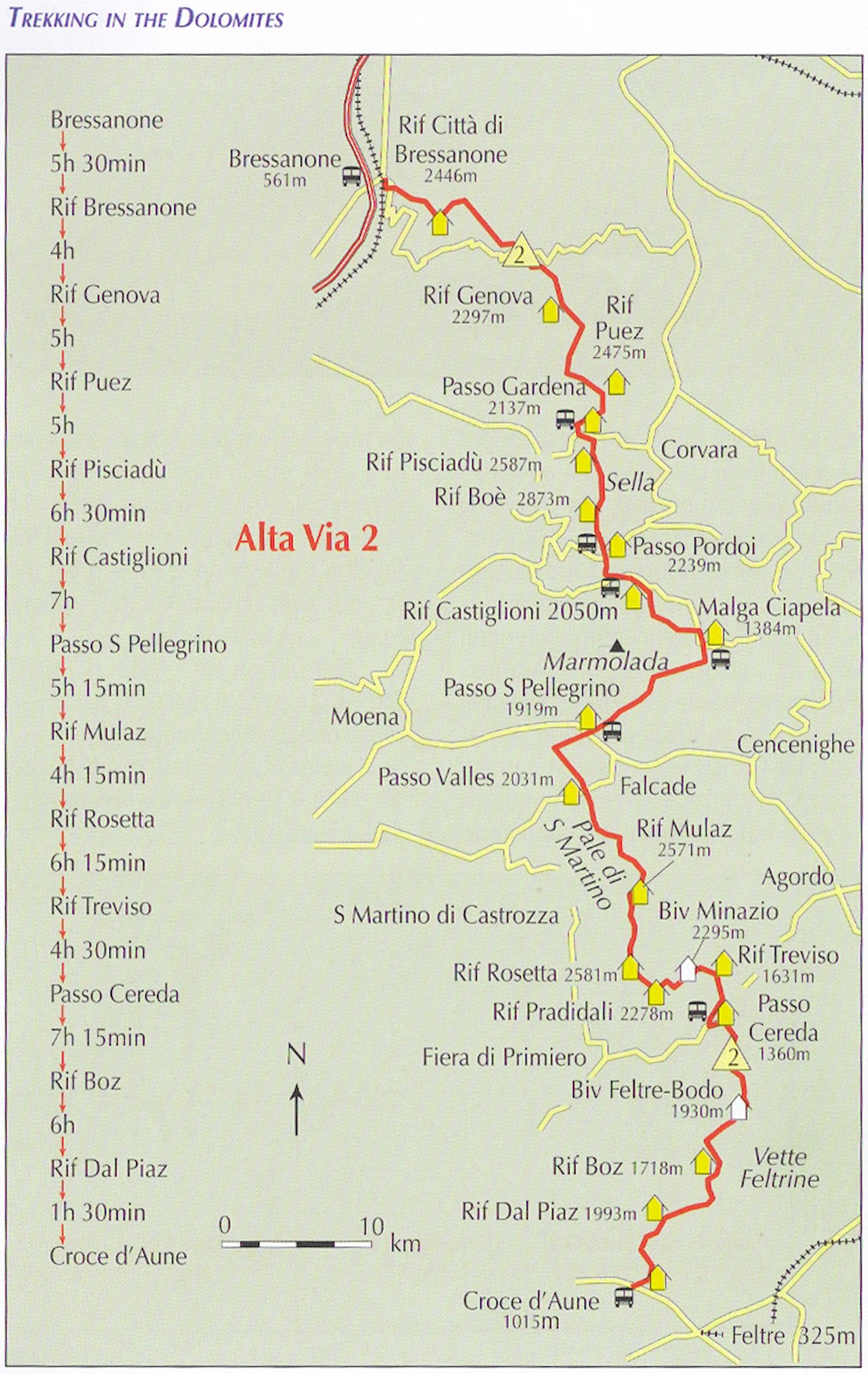

The Dolomites were spectacular as DL39 made its final approach into Venice. Suffering the window seat from Atlanta had been worth it. My dog-eared copy of Trekking In The Dolomites was in my lap, opened to the Alta Via 2. A short 10 months had passed, and I was back, making my way to Bressanone. At the foot of the Val Pusteria and the Brenner Pass, Bressanone is almost a small city, squeezed between mountains on either side. Here, the Alta Via 2 begins, climbing first a thousand meters to Plose, then heading south to Croce d'Aune, 180 kilometers distant. It is the westernmost of the classic Alta Vias, visiting seven distinct mountain groups between Val Pusteria and the plains of Veneto, truly a grand tour of the Dolomites. The next morning, I shared breakfast with Oliver, a young fellow from Paris. We had the same plan, but he would finish in seven days compared to my liesurely twelve. We headed up Plose to Rifugio Citta di Bressanone, my first night's stay. There he disappeared south across the pistes at a young person's pace toward Rifugio Genova. I was sure that, like similar acquaintances, this one would be ephemeral and I would never see him again.

Ringspitz and Le Odle Geisler

"Happy Birthday!" said the woman at the desk as she returned my passport. "Would you like coffee?" It was on the house and for a few moments delayed going out into the rain that had resumed. Yesterday's spectacular view of the Odle Needles had vanished, leaving these vast slopes to define a universe all their own. Eventually I could hear traffic, and soon reached the road crossing at Rif. Edelweisse where I stepped out of the rain for another 200 milligrams of caffeine and some strudel. The trail now followed a two-track with almost military precision for a couple of kilometers before taking to the long gully leading to Forcella de Pütia. At the forcella, the fickle weather did a 180 and hot sun blasted through the clouds. Thoughts of the subdued walk just completed were replaced with views looking across Alta Badia to the east. There was a couple sitting on a bench near the Crucifix. They had come from Munich and were walking the Traumpfad

Funtanacia

It was now clear sailing to Rifugio Genova along the high, cow-strewn slopes of Alta Badia. It was also still flower season and the almost level path was filled with blooms of edelwiesse, alpenrose and fields of salvia. With only a couple of easy kilometers remaining, I flopped down on a large flat rock, and, for the first time since arriving, relaxed and nodded off in the afternoon sunshine. The shadow from a dark cloud brought me awake. It seemed to be motionless. I mustered the neccessary initiative, collected my things and shuffled on to the rifugio. The desk was unmanned so I checked in at the bar and for the second night, had a room to myself.

Dinner was a quiet affair for there were only about a dozen guests and the wifi was down. My dessert was accompanied with a glass of grappa and unanticipated wishes for a happy birthday, this apparently being an event of opportunity; something to keep dinner and bedtime from bumping into each other. Several bottles of grappa in various hues, flavors and infusions appeared, some with berries and pine needles, and I think, fungi. None had labels. It was the American equivalent of moonshine and suggested a cautious approach and a small glass.

Piz Duleda

The high country at the head of the Val di Funes and Val de Lungiarü led to a shoulder from which the peaks of the Odle Geisler were now partially visible. A trail ascending a large scree-filled cirque led to Furcella della Roa, a break in the long ridge at 2617 meters. The last 100 meters went up a very steep side hill to the windy pass where I had to shield my eyes from the airborne grit coming up the other side. A quick look around showed a via ferrata going left along and through the cliffs and a path going straight down for some 300 meters before climbing back to the rim of the huge depression ahead. I dropped down and was quickly out of the wind shear and into patches of flowers. By the time I had reached the floor of the basin, it was again hot and sunny for the climb up to the next pass.

The view from this forcella was stunning. The Odle Geisler group which had been only partially visible since Plose was now aligned in full display to the west. East lay the moonscape of the Puez Plateau: a shelf some 4 kilometers in length with peaks rising 400 meters above to the left, a chasm known as the Val de Lunga to the right and Rifugio Puez at its head. Puez was the only place along the AV-2 where I had been unable to book a bed, muchless a place at the dining room table. It had been rented by a German walking group for their annual convention. Instead, I would be sleeping with the sheep in a meadow nearby. I had a light bag, pad and tarp for this occasion, the only time I would need this extra kilogram. Still, it was liberating to know that I could spend the night out, by choice or by chance. The dining room was deserted and I had just started eating a bowl of soup when a young woman asked if she could join me. I was glad that I had changed my shirt. "Please." She was a nurse 32, from Lienz, Austria, visiting friends in Selva. She had walked from Passo Gardena to Puez for lunch before returning down Val de Lunga. Her interest it turned out, was not in the Mozart on my phone but in ultralight gear and thru-hikes. My Hyperlite pack was like a fishing lure. I explained that I was working the ultralight concept into my budget a dollar at a time, and that the pack was an early acquisition. I told her I was camping before realizing that this was actually an invitation to inspect my cool tarp-tent and the laundry draped over a nearby boulder. A true nurse, she ignored the laundry and went to the tent. "May I?" I gestured, and she slid in. The clever design impressed her enough that, when we parted, she said simply, "It was nice to meet you. I really like your tent."

Crucifix at Forcella Crespëina

From Puez

the route continues eastward, making a long, arcing turn across the remainder of the Peuz Plateau before turning south along the AltiPiano de Crespëina. A tiny ithsmus of improbable looking ground tenuously connects these two geologically unique pieces of the Dolomites. I was frankly glad to be crossing it before anymore washed away. Even though it was cool and a bit breezy, people were swimming in Lech de Crespëina. At the end of the altipiano is the Forcella de Crespëina, the site of one of the most simplistically beautiful crucifixes in the Dolomites. To pray at its foot is a pilgrimage for some and the sole purpose for the walk from Passo Gardena.

The path to Üćia Pisciadù

As I walked south the trail became busy. Soon there were the sounds of motorcycles and I was looking down on Passo Gardena. Across the way lay the Sellas, the huge, flat-topped massif next in line on the route and magnetic in their grandeur. The Sellas resemble a mesa from the American Southwest, with a rampart of cliffs that impart a feeling of impregnability to the vast uplands they guard. Here and there these walls are breached by steep gullies. Path 666 is one of these, leading from the pass to Üćia Pisciadù. Lunch at Passo Gardena isn't a bad idea, for the 400 meters to the rifugio is by no means trivial. There is much steep ground, some cables, lots of loose rocks and plenty of people - all enough for me to fleetingly wish for my helmet and harness.

Üćia Pisciadù

Water is no problem at Üćia Pisciadù. There is a pretty lake just a stone's throw from the rifugio. It is also situated on a sweet spot overlooking Corvara and the Tofane to the east. All the terrain since Rifugio Genova is visible to the north. Even further north are hints of the Austrian Alps. This is all magnified as you climb out of the Pisciadù basin and into the upper reaches of the Sella. Here, the magic is in the lack of features. It would be a nifty trick indeed to find your way with a map and compass from one side to the other in the fog. However, in the bright sun, this was a distant problem, for Piz Boe stood starkly on the horizon, a landmark for all but the most cartographically challenged. A dot on the horizon gradually came into view. It was a signpost, indeed the only signpost in sight, held in place by the good intentions of a rockpile around its base and the implicit assurance that it pointed in the right direction. The faint sounds I heard were from a helicopter working on the construction project at Rifugio Boe. There were big plans afoot here and the helicopter, idling nearby, looked expensive. I distracted the staff from the construction activities long enough to get a coffee, then continued on my way to Forcella Pordoi.

To ride the funivia from Forcella Pordoi down 500 meters to the pass meant I would have to first climb the 150 meters from the rifugio to the upper station. This path was crowded with people in street shoes. Except for a couple of trail runners, the descent path was empty. I forfeiteted the opportunity for the stunning photo op from the top terminal and descended the scree slope, half-walking, half-glissading to the pass instead. It was a long way down, further than I had mentally prepared for, and I looked with some dismay at the slopes to the south of Passo Pordoi that rose to today's final stretch, the Viel de Pan.

The soup and sandwich from Rifugio Pordoi got me to the pass. I refueled with a plate of pasta and mushrooms then walked up the piste to Rifugio Fedarola and the start of the Viel de Pan . The Viel de Pan was a lucrative smuggler's route into highly-taxed Veneto and a path favored for safety over that in the valley - subject to avalanches, rockfall, and bandits. It also offers views to Marmolada

This was pleasant walking along the grassy hillsides with herds of sheep and an occasional hiker. Soon though, what was a mostly level stroll ended and the path descended steeply enough to warrant a couple of cables before ending on the road at Lago Fedaia and Rifugio Castiglioni, my bed for the night. It had been a wonderful day. The walks through the Sella plateau and along the Viel de Pan now seemed too brief. The day had flown by, almost effortlessly. The rifugio was a big place - more like a hotel and it was very busy. I checked in, bought a beer and went out for a walk along the lake. Lago di Fedaia

The dining room was full. Amenable to sharing a table, I was seated with an Italian gentleman and his daughter. They were from Treviso, and were also walking the AV2 as part of his vacation. He was very polite and cordial, yet disarmingly casual. She was young and quiet, perhaps shy, and listened intently as her father and I chatted about our newly-discovered common interests. Like Oliver, whom I had last seen at Plose, they were doubling-up on stages for a hero finish.. We said goodnight and goodbye - none of us thinking that we would see each other again.

The "classic" Alta Via 2 includes some high adventure. It climbs to a large notch on the western shoulder of Marmolada, first by a glacier crossing then along a series of via ferattas, eventually leading to a rifugio on the mountain's southern flank. Except for these passages, the route could be done without a kit, which was my plan. The alternate route circles the peak, first descending the streamless valley to Magla Ciapala then climbing west to a high pass, the Fórca Rossa. From there, a long descent follows to end the stage at Passo San Pellegrino. I had made the mistake of packing too light so I bought a fleece at a sports shop in the village and got some cash at the ATM. This would be the last opportunity to find either in the next several days. It was hot and there was gelato to briefly delay the 8 km climb up the immense Val de Franzedaz to Forcella Rossa. The walk down the road to the village had taken a lot of time, so I hoofed it up the valley, reaching the forcella as the storm, which had been building for an hour, began threatening in earnest. There were a couple of paths leading down: one went up slightly before descending a low-lying ridge. The other dropped straight down and with a short, cross-country jog, might rejoin the other. It seemed safer and worth the chance.

Fórca Rossa

I had been descending for only a minute or so

when I saw two people beating it back up the trail. They were my dinner companions and had taken the wrong path. I followed them back up, gasping to match their pace. At the pass, the smell of ozone filled the air. Before we could get into our raingear, the storm broke. We followed the uncomfortably exposed ridgelet down, but it was an agonizingly gradual descent and there was lightning and buzzing everywhere. The Italians were fast and soon disappeared. There were ground currents so I danced from one foot to the other to avoid them and switched to autopilot. They followed the lightning east, and in twenty minutes the storm was over. I sloshed down the path, now a small stream filled with hail and water. At a gate, there was a group of curious shaggy mountain ponies enjoying the emerging sunshine. The boss mare approached and nuzzled my hand for a treat. It seemed an offering was mandatory so I rewarded her with a caramel. The others then gathered round. I fished more from my pack and with my conscience now clear, wandered on. The last few kilometers rolled by in the dreamy afternoon light. As I approached the pass, I could see the Italians already well up the path on the other side of the valley, the girl's poncho flapping in the wind like a huge green flag. We had survived, and would find ourselves walking together through the dragon's mouth another day ...

I had made arrangements for the Alta Via 2 in February, but even then my first choice of lodging at Passo San Pellegrino was booked, so I ended up with a room at the Hotel Arnika. I presented myself - a soggy sight - at the desk. The guests were dressed casually, belying the 4-star surroundings which I thought were intended to attract a higher class of clientele, but now welcomed all as a matter of economic neccessity. The lady took my passport and a valet took my boots and wet gear to the drying room. "Would I like a token for the sauna?" "No thanks." I replied, only to discover that my room had neither heat nor hot water. I was given another in a wing that had both. I unpacked, hung my remaining gear to dry, and washed away the mud and pony spit. Dinner was a fancy mixed buffet with white-gloved camerieri who served hors d'oeuvres from silver platters, but the guests were in shorts and sandals. I hated how money had brought its social stratification to Jackson Hole, but I would be delighted to see this refreshing incongruity repeated many times in Italy.

The sky was clear but the air was dense with moisture as I followed the path my acqaintances had taken the day before. It was tempting to take the cable car to Col Margherita, but I had not come to ride trams, and I was not yet tired enough to compromise my lofty - but flexible - standards. Besides, I had the whole day to get to Rifugio Mulaz. Col Margherita (in Italy, Cols are actually peaks) was home to an expansive ski area, so much of the next few hour's walk was across pistes and above a large hydro project, but the emerging views of the next range of peaks to the south softened the touch of development. A mix of paths and two-tracks took me to the road at Passo di Vallès and it's rifugio, reputed to be among the best in the Dolomites. It was quiet and I was hungry, despite stuffing myself with cialde con panna at breakfast, so I stopped for a beer and and a sandwich. Though it was still early, clouds were beginning to develop. The rest of the day would take me into the peaks of the Pale San Martino with their reputation for ruggedness and mists. I started off, hoping to avoid the dreaded mists and arrived at Mulaz just as they were obscuring the towers surrounding the rifugio, and indeed, it seemed to happen in just moments - in one, they were visible, and in the next, you would not know they existed.

There was smoke coming from the chimney. As I checked in, I noticed two glum people sitting near the stove. They were the Italians. Their progress had been stymied by the weather. "Yesterday we watched for you until we were sure you were safe." he said quietly. We occcupied opposite corners of the dorm. Later, as I unpacked, I came across postcards I had brought along. I intended to send these to friends back home as a joke. "Want to see some postcards from Wyoming?" I asked. Yes they did. The girl studied each one intensely - they were more than pictures. I recognized the passion in her quiet gaze, and I wondered where it would lead.

It was becoming a reunion. Someone came in from the murk. It was Oliver from Bressanone! Unsure of finding Rifugio Rosetta in the featureless surroundings, he had retraced his steps through the fog and at that moment might have been the happiest person in the room. He said it was only through luck and the red markers thay he had he found his way back to Mulaz. I looked out the window and was reminded of author Shirley Jackson's Sundial . There was nothing there ...

Passo delle Farangole

The morning was dazzling and the towers of the Focobon - in and out of existence yesterday - had only a few wreaths of mist lingering in the shadowed northern rock; only in this moment fully revealed. We all said our farewells (again) and by the time I had finished the switchbacks to the forcella above the rifugio, the Italians were already making their way up the final slopes of Passo delle Farangole, the girl's white helmet a dot against the dark rock. There was another American, fast as well, but uncomfortable on the snow. I followed him across the small patch. He did fine, then quickly disappeared as well. I gawked, and took some photos, and the cirque became quiet. More switchbacks, some cable and ladders took me to the sharp notch of the forcella and the zenith of the day's walk. There were stunning views both north and south, fine enough to wish for a camera better than my simple point-and-shoot (TGFF) .

There were places still to go on this wonderful day, and that meant once again going down before going up. The descent from the forcella followed a series of ladders to the top of a steep scree ramp. There were dots in two directions, one to the left - down the ramp, the other to the right toward the remnants of a barely visible glacier. I chose the one to the right and in 50 meters, found the "THE" Italians) would be long-gone, but the American should have been visible. I looked left and spotted him at about the same time he saw me. "Are you on the right trail?" he shouted. "Yes." I said, there being no reason to shout. He started across the slabs. I pointed up, the way he had come. When he arrived, we studied the route on the map. He nodded, smiled, and was off with another wave. The peaks on the map were on display to the south and I spent a few minutes admiring them and their names, hoping I would remember them.

This path, the Sentiero della Farangole , is squeezed between the cliffs of Cima delle Comelle above and those of Val delle Comelle below and follows the valley's ramparts to its head. It is an exhilarating walk, both in its beauty and its character, perched along cliffs and steep hillsides for nearly 5 kilometers. It then wanders up slabs and terraces along the northern edge of the immense plateau of the Altipiano delle Pale di San Martino - eventually leading to Rifugio Rosetta. Here, you are returned to the bosom of civilization, for the upper station of a funivia is a mere 500 meters away. It was mid afternoon and the rifugio was crowded. The tables were full so I took off my pack, sat down against it on the deck, closed my eyes to the sunshine and nodded-off. "Beer?" someone asked. It was Karl, the American. "Thanks." he said again, and sat down. "No problem. Milwaukee?" I queried. "Isn't everyone?" then, "Are you really from Wyoming?" I said no to the first - I knew people from Madison, and yes to the second. There were a half-million of us, well-dispersed and for the most part, as happily oblivious to the outside world as we were to each other. "I leave once in a while, just for socialization." I joked. He took me seriously, suggesting a need for another beer. As we nursed it, he explained that he had never been west of the Mississippi. I ribbed him about being safe from savages and bears, but that bounced-off too. I wasn't sure that another beer was the answer.

The Alpine Guide

The breakfast crowd was small in comparison to that of last night's dinner. Karl and I walked together for a short way before parting with a "See Ya." We were now friends. The path could only descend and it did so in dizzying fashion, losing 500 meters in less than a kilometer of switchbacks, stacked one atop the other. When it became impossible to go any lower, it cut south, finding an unlikely line across a series of butresses to the long via feratta leading to Passo di Ball. There were two sections, each with several spans of cable. The first was a mere warm-up for the second which crossed the flank of Cima Pradidali, following small seams across its sweeping 50° skirt. It was a spectacular place to be. I looped a piece of webbing around my waist and clipped in. All to soon the fun ended at a scree slope that lead to the pass. John Ball was Irish, a failed politician, exemplary naturalist and the first president of the British Alpine Club, known simply as the "Alpine Club". He climbed extensively in the Dolomites, making many notable ascents including the first of Monte Pelmo. A plaque at the entrance to Rifugio Venezia commemorates this ascent of the peak that towers above. His book "The Alpine Guide", published in 1873, is still sold, and its detail and timeless humor make for great reading. I think of him as a man who knew when to cut his losses and have fun - a dirt-bag of his time.

This was the heart of the Pale San Martino and I spent more time than I should have, gazing. I could see Rifugio Pradidali below, and a cappuchino seemed reason enough for a quick stop. I arrived to find Karl doing the same. I ordered one, and a huge pastry - and made short work of both. He was in his harness, headed for Feratta del Porton and points west. I wished him good luck and took the path northeast, following a pipe that eventually led to Lago Pradidali, the rifugio's water supply. The lake looked much smaller in real life than it did on the map and I wondered about the fate of the little rifugio without it. The cutoff to Passo delle Lede was obscure, and missing it would have added 6 kilometers to what was already becoming a long day. I found it but I was tired and struggled up the steep ground to the ridgecrest.

Altipiano delle Pale di San Martino from Passo delle Lede

At nearly 2,700 meters, Passo delle Lede was the high point of the day. Far to the north, I could make out Passo delle Farangole and even further on the skyline, Marmolada. My thoughts were caught up however with the 1200 meter descent that lay at my feet. I looked at the map. The path seemed straightforward, but I wanted to avoid any uneccessary wandering nonetheless. It was well marked and in an hour I reached Bivacco Minazio. The spring was nearly dry and the place seemed abandoned. I passed a small mound of broken aircraft parts and the memorial

Campaniles

Rifugio Treviso was on the forested north-facing slope of the chain of peaks that marked the southwestern end of the Pale San Martino. It was cool and pleasant along these first two kilometers of level path. Someone from the rifugio was gathering fungi and during a brief chat he pointed out the varieties that he would collect for the cook. This was a daily ritual during the season. He said that in some parts of the country there were strict rules that defined areas where only local residents could collect fungi, a resource that supported local economies. I now understood the signs I had seen scattered in the woods and thought as I walked along the flower-strewn path, there was more to the widespread collection of mushrooms than met the eye. The path reached a junction and turned straight up the hill, climbing for 500 meters to Forcella d'Oltro on the crest of this spine of peaks. From this perspective, the Val delle Lede was huge. To the south lay the Cimonega and Vette groups and for me, it would take three days of walking to complete them. The trail now dropped straight down for 200 meters before turning south through a forest of "Campaniles" , skirting the cliffs of this persistent ridge for nearly five kilometers before abruptly diving the final knee-knocking 500 meters to reach Passo Cereda. Other than a small group of cyclist on the patio, Rifugio Cereda was quiet. I checked in and got a beer, succumbed to an impulse for potato chips and took them outside to watch the sun disappear.

The Cimonega and Vette Feltrine are wild and isolated, rivaling the "Path of Silences" in this respect. The paths are in places primitive and difficult to follow, particularly in bad weather. These are good reasons for many to make Passo Cereda their finish to the Alta Via 2. I had found only a couple of accounts describing these last two stages, and it was hard to tell how much of the content was from actual feet-on-the-ground experience. "This could be, You may find, It is possible ..." phrases sprinkled throughout the accounts made the area all the more mysterious and alluring, so I crossed the road, filled with anticipation - and a touch of apprehension - to begin the 700 meter climb to Passo Comedon. I was alone in silence for two hours before the bells of Sunday Mass rang out in the valley below. On the map, the trail had changed from dashes to dots, and indeed, the ground now approaching the pass had become steep and semi-serious - a hard, gritty surface that made each footstep tenuous. By the time I reached the pass, I concluded that there must be three Masses: the bells had sounded on three separate occasions, the last marking midday and my final steps to the pass.

A Closet Optomist, my hopes for better footing were dashed as the path now wound its way through boulders, headwalls and loose scree around the shoulder of Piz di Sagron to Bivacco Walter Bodo, a tiny red structure anchored to the ground with cables at each corner. Bivaccos usually mean water and sure enough, there was a clear, cold stream with a pool nearby. I was half way through the day and with one last hill, most of the difficulties were behind me. I enjoyed (tolerated) the cold water as long as I could, then returned to the deck of the bivacco, ate lunch, and dried off in the now-dwindling sunshine. In this collection of nearby cirques, there were several respectable peaks with respectable looking rock. I wondered if the bivacco's purpose was as a base camp for climbers or simply shelter for visitors passing through this remote country. Afternoon clouds were building and I thought it better to be in the fog at Rifugio Boz than wandering through it along the way, but by the time I reached Col dei Bechi, all I could see was the sign, telling me I had arrived - seemingly nowhere. The trail however, was distinct, crossing a series of steep, grassy hillsides that fell away into the mist, softening what I knew was significant exposure. This blissful period ended as the sun broke through and the slopes below became visible. It was a long way down and the path, which was deceptively cozy in the fog now seemed ridiculously narrow. The English refer to "comfort" in these circumstances as "having a head for heights." I think of this more as reaching an uneasy peace that has everything to do with the yin of confidence and the yang of discipline - and nothing to do with comfort. It is comfort, not caution that brings on trouble. I followed the grassy precipices of the "Troi dei Caserin" to their end at Passo de Mura and could now see Rifugio Boz in the large meadow below. There were fences and cows, and I would soon discover that Boz was a real working dairy. In addition to the cows, there were people drinking beer and playing Bocce, but I was hot and went inside to sit at a table. As I drank my first beer I noticed the paper place mats with a rendering of Sasso Scarnia. It was the view across the meadow and the theme of the rifugio, replicated on scarves, mugs and t-shirts. At 2,200 meters, it would be the last significant peak of the route. Not surprisingly, the main dishes on the menu were all variations on cheese, and why not? It was a commodity in plentiful supply, fresh and always well-prepared. Italians know how to do cheese. The bunks were in a converted cow shed - a stone building, cool and quiet. At dinner, I listened to a couple who were also planning to do the walk to Rifugio dal Piaz. There was a short stretch of narrow, exposed and unprotected ridge that had her concerned. It was rubbing-off on me. "The wind can blow you off the mountain!" the woman said, pointing to the photo on the wall, and it did look terrifying. "It's only a few meters," the guy replied, wearily. He was not helping things along, and I thought if not careful, could be looking for another companion. "Non è male," said the guy behind the bar. I didn't understand the rest of what he said, but it sounded reassuring and she seemed mollified.

It was another bluebird day. Morning mist filled the meadows below. It was muddy from recent rains, and I was stung by the fence twice trying to keep my boots dry. Just below Passo di Finestra I met the couple from last night. They were descending and silent as I stepped aside to let them by. At the pass it became clear why they had turned around. The landscape was steep and wild and lush, the path now following a series of narrow, discontinuous ledges (some overhanging) out of sight around the first corner, and from the looks of the terrain, through more of the same. The view to the south was unexpected. The Dolomites were melting into a chain of hills wreathed in mist. Beyond them I knew, were the plains of the Veneto and the Adriatic Sea, but these were lost in the summer haze and air thick with humidity. A short distance up the path was the first overhanging section and a plaque bearing a name and the word "morte." I took off my pack and stowed my umbrella where it would not protrude, and continued along the series of overhanging ledges. Eventually things opened-up and the walking became easier. There was a dog-leg in the ridge ahead, and I knew this was where the knife-edge would be. Sure enough, the traverse along the ridge climbed to this dramatic point. The path ahead was about ten meters in length and perhaps 1/2 meter wide, ending with a series of steps carved into the rock wall ahead. It was very exposed on both sides. I could understand why someone would take one look and go home. At the top of the steps, I turned around to take a picture, but the drama had vanished with the perspective. The path now followed the ridgecrest of Sasso Scarnia almost to its summit before breaking off to reach easier ground below. Now in the Vette Feltrine, I would follow its west flank for almost 8 kilometers in total solitude along ridges, bowls and fields of flowers before reaching Passo Le Vette Grande. There, I sat for nearly an hour, looking down on the rifugio and far below, Croce d'Aune and the road to Feltre.

"May I see your passport?" asked the woman at the desk. She looked at it once, then once again. "One moment," she said, and went into the back. I wondered if I had somehow landed on a watch list, but she returned with a smile and a note. It was from the Italians, with their email addresses and an invitation to write. I was touched by this kind and unexpected gesture. I tucked the note in my passport and got on with a solitary and somewhat forced celebration of the past two weeks. There were others at the rifugio, but they had all come up from the valley. I was suddenly alone with my beer and pasta alla boscaiola - and uncharacteristically lonely. It was time to go home.

Last Day's Walk

The descent to Croce d'Aune was more enjoyable than I expected. Breakfast and the up-tempo nature of morning in a rifugio had chased away last night's self-pity, and it was again, a very nice day. The descent initially followed an old military road, full of switchbacks engineered into the steep hillside. About half-way down, the path left the circuitous road for a more direct descent to the village. It passed through beech forests and meadows. Here and there, it was decorated with wimsical wood carvings, a practice that I would come to discover, was quite popular in this country where sharing happiness was an art form, practiced in many ways. The path ended at a lane with a Cucifix and sign pointing up to the rifugio and down to the town. The Alta Via 2 was over, simply and without fanfare, at the end of a quiet street.

The bus wouldn't arrive for two hours. After 30 minutes at a cafe across the street, I decided to hitch rather than wait and drink. There weren't many cars, but eventually one stopped. It was an older gentleman and his young wife, or perhaps girl friend (this was Italy after all - the world's last hope for romantic illusions). As I was loading my pack into the hatch, a couple arrived - beaming hopefully. The driver shrugged and they added their packs to the load. We squeezed in, acknowledging our collective bouquets with weak smiles - the girl a pleasant buffer in the middle. I took a look at the driver who was wearing a Conte beret and driving gloves - and buckled up. He was an excellent driver, and even with the car overloaded, he put it through the steep turns without a single groan from either the tires or his passengers. We flew into Feltre. "Tourist office?" he asked. "Si, Grazie." and we were there. The girl at the desk was a stickler about the pins. I had stamps from the rifugios, signed the book and received mine, but the others had camped and could not establish their authenticity. I had my shiny souvenier in hand and figured she couldn't repossess it so I said, "I saw them at ...," and she relented. Outside, I asked him what he had thought about the route. He looked at me and smiled. I had called Hotel Doriguzzi from dal Piaz to ask if I could come a day early. I could, so I did - arriving just as it was getting unbearably hot. The AC was working and the mini-bar was filled with beer. Life was good - really good ...

I spent two interesting days wandering in Feltre, with its huge street market, predictably excellent food and fascinating history. At the train station, I asked for a ticket to Venice. "Don't take the train from here," the agent said. "Take the bus to Montebelluna. From there the train will take you straight to Mestre." This sounded pretty intricate at first, but he assured me that it would be easy and it would eliminate the time squeeze of taking the train through Belluno. "Just follow everyone." he suggested casually. This all worked out and as I passed through Treviso, I thought of the Italians, and their invitation. When the endless day finally ended, I was back in Jackson Hole - in time for the sunset - and already thinking about the Alta Via 3 ...

"Failure always comes with a personalized self-help kit. So does success ..."

- Unknown -

![]() will do just what it says and take you down another rabbit hole.

will do just what it says and take you down another rabbit hole.

;

;