☙ 7 September, 2023 ❧

The Wind River High Route, Haute Route or Highway is a north-south route in the Wind River Range of western Wyoming that closely follows the Continental Divide for about 90 miles. It is widely considered to be the finest non-technical distance walk in the United States. The Wind River Range is a roughly 100 by 40 mile uplift containing over 150 distinct granitic peaks, of which 37 exceed 4000 meters, extensive glaciers and hundreds of lakes. Upon reaching 3000 meters, the route remains above that elevation for its entirety. About 2/3 of the route is off the established trail system and typically takes 7 to 10 days to complete. There are two popular flavors and a number of variations of the route first completed by Alan Dixon and Don Wilson in 2013. They walked from the Green River Lakes trailhead south to Big Sandy Opening, a distance of about 85 miles. A popular alternative to the Wilson-Dixon route is Andrew Skurka's "Complete Wind River High Route", lying between Bruce Bridge near Lander and Trail Lakes near Dubois. The Skurka route is a few miles longer, includes a couple of gratuitous, 13,000+ ft. peaks, and keeps mostly to the east side of the continental divide while the Wilson-Dixon favors the west side. Peak-bagging is an option on both routes. The Skurka route also passes through the Wind River Indian Reservation which requires a permit that can be most conveniently puchased at the tribal headquarters in Fort Washakie, but that stage (from Photo Pass to Europe Pass) can easily be bypassed by staying west of the divide. Both routes can be done in either direction but most favor a southern start for the Skurka and a northern start for the Wilson-Dixon. Neither route can claim passage through undiscovered country. Rather, they are ingenious weddings of sections of the range that have most certainly felt the past footsteps of those drawn to the area to explore, survey, plant or catch fish (there are no native fish in the high lakes), and graze sheep and cattle. The open nature of the terrain, particularly in the southern portions of the range, allows for many variations. The section of the Skurka route from Alpine Lakes north is spectacular.

For better or worse, this unique and fragile piece of the planet has been discovered, and not everyone is happy about it. In just a few short years, social media, geotagging and word-of-mouth have transformed the relatively few, accessible places from local hangouts into tourist destinations, management nightmares and the backbone of local economies. Ultralight gear, improved air travel, guides, packers and shuttle services to and from the trailheads are as convenient as your credit card. If you spend any time at all talking to locals in the gateway communities, you might come away puzzled by the range of responses; there is an attitude of fierce protectiveness, both for the land as well as its importance as the region's cash cow and local playground, resentment of the federal presence, tribal control of a large area of the range, and frankly, for you if you stay too long. Add to this mix the state's agressive promotion of tourism, and the bumper sticker, "Welcome to Wyoming - Have a safe trip home" loses some of its homey ring. There is a good side to this though which borders on magic: The Winds are immense, and though the bathtub ring of overuse is near to becoming unsalvageable, a single day's walk inward past the established trail system and campsites, and you will have passed the event horizon of distance and elevation. If you see anyone at all, they may well be quiet, friendly, aware of their footsteps, and perhaps a lot like you. With a little luck, you can immerse yourself in this rare isolation for a week. This is not to say that you won't encounter people in numbers. The comparatively benign southern section of the range is peppered with east-west passes, attractive to horse parties, school outings and perhaps most notoriously NOLS, a sort of outdoor bootcamp based in Lander, WY that has cycled thousands through its Wind River programs over the years.

Weather forecasts based on surrounding towns can foretell major changes but they cannot be relied upon to predict localized mountain phenomena like thunderstorms, snowshowers and hail. Even more counfounding, spot forecasts can be wildly misleading. Snow rain and sunshine can all occur simultaneously within a mile or of each other and can change in the space of minutes. This is particularly true of thunderstorms. Add to the mix elevation and the proximity to the Continental Divide, in places exceeding 4000 meters, and you have the true definition of a WAG when it comes to weather forecasts. The expansive and often featureless nature of higher terrain also makes lightning unpredictable. On the high ridges and particularly along the divide, beware. Know the closest route to lower ground and watch the weather. Electrical storms can literally materialize from nowhere in a matter of minutes and move quickly, paradoxically often in the direction you are retreating. As a last resort, when everything is buzzing and your hair is standing on end, separate yourself from your pack and poles, lie flat and pray or curse, whichever is most appropriate for you. There is no season immune from major weather events, but fall is most notorious for delivering foot-deep overnight snow storms. It is common for a mid to late October storm to end the hiking season.

Mosquitoes, Mosquitoes, Mosquitoes...

To appreciate the mosquitoe and its reputation as the "apex predator" of the Winds, it helps to know a bit about the geology. Imagine the Winds as a big, thick pancake topped with a generous pile of whipped cream, all situated in the middle of the high plains of western Wyoming. The pancake represents the skirt of impermeable bedrock from which the peaks (whipped cream) rise. Add some glaciation to carve canyons in the peaks and gouge out depressions in the bedrock to form a few hundred lakes, ponds and bogs. Eventually the climate warms and the glaciers retreat. Allow a few thousand years more for the formation of some soil so grass, moss and sedges can take root and provide resting and hiding places for the bugs. Jump to the present, lets say July. The mountains and the surrounding skirt have been shedding their winter snowpack. The skirt is now mostly snowfree, the trails are navigable, and the streams and rivers are rushing. Water fills every depression and saturates the thin ground cover. The eggs of "Aedes pullatus", (click on the image for more info) deposited in the waning days of the previous season have hatched and completed their larval stage, now emerging as adults from this mother of all watery nurseries. They are beside themselves with reproductive frenzy. Even if the temperature occasionally dips below freezing, the hardy little beast has had a million years to adapt to cold. They can often be found wriggling their way out of the thin skin of pond ice formed during a previous night's freeze. Within hours though, the casualties are a mere fraction of the growing multitudes of the newly-arrived which need just one thing to continue the cycle. The males are only there for the sex, but the females are out for blood. As if their overwhelming numerical advantage was not enough, Aedes Pullatus has a targeting system rivaling a stinger missle. It not only detects heat but minute levels of CO2 as well. This is of course the definition of an overheated, panting backpacker, and against this ancient bioweapon, only DEET, a vile petrochemical capable of turning your sunglasses into goo, and to a lesser extent the more benign Picardin have been found capable of effectively befuddling this system. Savvy folks will take a bug hat and even a netting tent to provide a portable no-fly-zone at camp or at stops along the way. You can buy clothing that has been infused with permethrin, or get a bottle and treat your outer clothing yourself. Permethrin is a toxic insecticide. It works by poisoning the mosquitoes faster than it poisons you, so don't apply it to clothing worn next to your skin, and keep it away from your cat and your goldfish.

Mile 169, US 191

'...Today has finally arrived. It has taken two years to earn your ten day vacation and you've driven to the Winds straight through from Columbus, Ohio, making better time than FedEx. The radio has been feeding you CW music since Taco John's in Cheyenne. Two hundred miles later, you've adjusted to the tacos and the tunes, and you're finally headed north, gazing at the endless unfolding panorama of snowy peaks, letting Wyoming's contribution to self-driving technology, the rumble strip, keep you on the road. When you stopped by the outdoor shop before hitting the trail, the girl behind the counter asked if you needed DEET because her boss instructed her to ask that of every customer, but you read somewhere on the internet that the stuff caused cancer, blindness, impotence and road-rage. "Lame" you said to yourself as you left. "What kind of outdoor shop doesn't have citronella or the Skin So Soft mom smeared on me as a kid?" Someone was leaving just as you arrived so you lucked out with a parking spot at Trail's End. It was late and warm but the bugs didn't seem that bad so you started the 12 mile walk in to Island Lake. Within the first hour, you had covered all but an eye slit so you could see where you were going and discovered that stopping was not an option. Brushing the bugs from your covered face left bloody marks on your hands and you recalled stories of livestock going berserk from mosquitos. After what seemed an eternity - unable to swat and run at the same time, stop to catch your breath or even pee - you retreated back to your car. Heaving your pack in the passenger's seat, climbing in and slamming shut the door in one surprising coordinated motion, you finished-off the dozen or so remaining kamakazes. With the killing spree complete, you found yourself (a) hoping the faintness was from altitude, not blood loss and (b) wondering if you should visit the clinic before finding someplace in Pinedale that sold DEET at midnight because three days of your vacation were already shot. ED wasn't that big a big deal anyway ...'

Suspect that anyone boasting of a mosquitoe-free mid-July trip to the Winds might have taken a wrong turn and actually been in South Dakota. The west is a big place.

Taking advantage of a forecast for a cold snap and prolonged spell of good weather, I began the High Route in early September. After a forced 6 am start, spending most of the day spotting a vehicle and wanting no part of it in the first place, the relief on my wife's face was palpable as she headed back down the shock-busting Big Sandy road without a backward glance. Sidestepping the cloud of dust, I began my south to north journey, preferring the sun to my back and to camp the first night in the Cirque rather than along the Green with its increased bear activity. Within a minute all systems had rebooted and I was living in the moment. Like the Green, the walk along the Big Sandy River offers a gentle beginning to any adventure. With its glimpses of Wind River grandeur, Big Sandy Lake is where the warm-up ends and the fun begins. It was the Tuesday following Labor Day and still busy. The departing cold front made for cool and breezy walk up to Jackass Pass. I followed the last group of young, oxygen-starved stragglers through the "boulder problem" at Arrowhead Lake and up toward the pass. They turned out to be a young couple on their honeymoon and had driven straight through from South Bend Indiana, stopping only for gas and restrooms. Both had been up since the ceremony and as the woman said, "We were 50 miles down the road before we finished our cake". The groom was managing only 10 steps between rests but the bride, obviously in better shape and seemingly unaffected by the altitude, was determined to connsumate their marriage in the Cirque of the Towers according to the plan she outlined. I suspected there was no plan B and that anything short of a camp at Lonesome would be a cruel disappointment. We reached the pass. "It's all downhill from here" I exhorted encouragingly before realizing what I had said. He was wasted, she remained a pillar of matrimonial determination, and I feared that anything further from me would only make matters worse. I offered to follow them down to the climber's cutoff and hopefully point out a campsite. After a few minutes of downhill, progress improved and we reached the cutoff. As I pointed out an empty spot just outside the 1/4 mile limit, the woman turned and embraced me. What I assumed to be relief and the beauty of the Cirque working its magic I then realized was a touching gesture of gratitude. She had tears in her eyes. I had simply failed to appreciate how important being here was to them. We shook hands, exchanged more embraces and I kissed the bride before we separated. I watched them descend for a minute or so before going on my way. Though the Cirque was predictably busy, I found a spot to camp among some climbers in the meadows below Pylon Peak. The departing weather system exited around midnight with a ferocious hour-long thunderstorm replete with all the trimmings. Not bad for the first day. Drifting off, my last thoughts were of the honeymooners and how we had been the most ephemeral of friends - we had never told each other our names.

Except for a few climbing parties, all seemingly headed for Pingora, everyone had apparently slept in after last night's excitement for I saw no one until well up the Texas Pass trail where I met an older couple who said they had bivvied just below the pass. They were cautiously making their way down to the lake to regroup following last night's storm. The fellow warned me of the dangers of the terrain above, which I thought odd, then began admonishing me for traveling solo, ticking off each possible "don't you know that this could happen" catastrophe on the list while, who I assumed was his wife, nodded or shook her head with each of his bullets. Yearning to respond to this dressing down with something clever but sensing that doing so would only precipitate an even more comprehensive lecture, I instead thanked them for their concern and continued on, thinking that if I were looking to commit an irresponsible act, Texas Pass at 3500 meters in a thunderstorm would certainly make the short list. During the twenty minutes or so to the pass, I wondered how many others had unintentionally danced with the devil during last night's storm. While a ranger in Grand Teton National Park, it was almost a certainty that we would be fetching someone from the mountains following a storm like last night's. At the pass I was a greeted with a stiff, cool breeze from the north. Sweaty, and with no convenient place to linger out of the wind, I made my way down to Texas Lake, passing several parties laboring up the steep, loose ground, headed to the Cirque. I met two more people crossing Washakie Creek on an otherwise empty trail to Pyramid Lake. By afternoon both the wind and clouds had disappeared. It was still early when I arrived at the lake which looked to be deserted as well. The day had been a relatively easy one and I considered scrambling up Mt. Hooker to look down its immense north face, but by the time I had set up camp, a second look at the 500m of slabs and talus made a swim and a nap in the afternoon sun seem much more appealing. There were fish here, and it only took a couple of minutes to catch two 8-inchers and stretch tonight's noodles.

East Fork Divide

I discovered that I had shared Pyramid Lake with one other quiet party camped across the water, and we acknowledged each other with a wave as I left. The marked trail ended at the lake but an obvious use path heading west to the East Fork River divide and north along a broad bench above Desolation Valley appeared in its place. At this divide, the view is stunning. The Wilson-Dixon route is visible as a slight disturbance across the grassy meadow to the north. While there are lakes on the floor of this treeless valley cradling the headwaters of the East Fork River, it is the impressive 3 km long wall of 3700 + meter peaks marching from Mt. Geikie, Peak 12,183 , and Peak 12,187 with its curious giant black "M" intrusion, to Raid and Bonneville peaks that not only define the drainage, but stand as the westernmost bastion of summits rising above the skirt of granite that encircles and isolates the range from the Wyoming sagebrush plains. As you walk up the vally, alpine tundra replaces scrub pine but that soon gives way to headwalls, glacier-polished bedrock and finally the slopes of extra-large talus through which lies the path to the aptly-named "Pain In The Ass Pass" separating Raid and Bonneville Peaks. At near 3600 meters, this pass overlooks a broad swath of the southwestern Winds, the distant high plains and the mouth of Bonneville Basin directly below. I took advantage of three bars on the phone and reported in before descending into the Basin. The descent wandered through gentle headwalls and scree to the basin. There I caught the well-defined path that led past the lakes and up to my camp for the night at a lilliputian pond in the meadows below Sentry Pass.

Like the headwall guarding Bonneville Lake, the climb to Sentry Pass had just enough mildly exposed hands-on ground to remind me that I was by myself. From the broad pass, still holding an untracked snowfield, the view of Pronghorn Peak and the Middle Fork valley was overwhelming. Though I have been to many awesome places on the planet, the "high lonesome" of the Winds posesses a unique power to reliably blow my mind with each visit. The descent past Lake Donna into the Middle Fork fully reveals the immense east face of Pronghorn Peak and the phalanx of towers bounding the west side of the Middle Fork valley, a somewhat eerie mirror-image of the East Fork's Desolation Valley visited just yesterday. The "Middle Fork" refers to a tributary of Boulder Creek which, despite its vast drainage, changes from a nearly impassable spring torrent to a mere trickle that can be stepped over in many places in late season. I'm sure there was a straightforward route down to the east shore of Lee Lake, but I managed to miss it, instead electing to milk my elevation and ignoring the adage that the easiest passage in the Winds is almost never a straight (or level) path. A good hour of thrashing through willows and subalpine scrub pine finally put me on the trail along the shore of the lake from where I could look back at the now obvious line from Sentry Pass. As I followed the well worn use trail around Middle Fork Lake, I briefly reconsidered shortcutting to Bewmark lake for the planned walk over Photo Pass and the ensuing illegal dash through reservation country. The terrain looked uglier than what I had just descended and one of the few parties I had talked with when descending Texas Pass had come from the Milky Lakes where reservation officials had checked their permit. With the shortcut to Bewmark lake now looking foolhardy, I changed plans and headed overland instead to Hall's Lake. Again, it was easy to find the use trail going north from the official trail since there were many cairns along the way. It soon became apparent why they had been placed in such numbers. The next mile was a labyrinth of streams, bogs, ponds and deadfall and I appreciated the fact that it had probably required significant planning and considerable effort to establish a single path and save those to come the effort of finding a way through what was an already fading maze of false trails going nowhere. Soon the way was clear and it was pleasant walking the rest of the way to Hall's Lake which I reached just in time to set up camp and enjoy a nice sunset with dinner and a nightcap of Blanton's.

My original plan had been to combine sections of the Wilson-Dixon and Skurka high routes, as well as substituting the Alpine Lakes stage with what seemed an obvious line between Upper Golden Lake and Island Lake but for which I could find no information. The now-abandoned stage through the Milky Lakes basin and back up to Europe Pass was to be followed by a walk from there over Europe Peak then along the Continental Divide to Hay Pass. The new plan would now take me from Hall's Lake into upper Europe Canyon. I had the choice of reaching Europe Canyon via the natural contour through the low pass east of Medina Mountain or climbing out of the Hall's Lake basin due north and descending into upper Europe Canyon via a high pass on the ridge separating the two dainages. In spite of previous visits to the upper reaches of Europe Canyon, I could not recall if the pass I was studying high on the ridgeline would actually "go". After some time mulling the decision, I concluded that the distastful thought of retreating from the pass in the event of questionable terrain would only encourage risk-taking simply to save some time, and of that I had no shortage. As it turned out, the lower traverse into Europe Canyon and the walk up to its head was a pleasant stroll. As a significant passage across the great divide, I had expected to see someone in Europe Canyon but the place was empty. Once I reached the upper reaches of the canyon, a close examination of the descent from the pass I had considered earlier looked intricate but doable. I congratulated myself for my wisdom/cowardice/restraint, hastily set up camp on the shore of the upper lake and jumped in the tent just before the afternoon thunderstorms arrived. I had never used the tent, a 2 year-old Zpacks Plexamid in the full-on conditions it appeared were about to develop and I was a little skeptical with a tent weighing in at only 400 grams holding up in real life circumstances. As the storm rolled in, so did my eyes as I watched the translucent dyneema fabric strain under what I estimated to be 50 knot gusts. I briefly thought about space-age technology, Saran-Wrap, and 2.5 mm guylines, and whether my tiny titanium stakes would stay in the soft ground. The door closure design concerned me the most though because it was a simple set of toggles that held the two panels together with a two inch overlap. I was certain wind from the right direction would force water through the overlap, but whoever came up with such a minimalistic and improbable design had apparently tested it, for as the wind swung from one direction to another, the overlap stayed stubbornly snug. I sent a nice note to the company after the trip relating my experience. They returned an even nicer note, with congratulations (...for either my wise purchase or my survival, I could not tell), and assurances that the tent had been tested in much more "robust" conditions. How much was "much more robust...?" They didn't say but I guess you get what you pay for. Whatever knowledge Floridians might be suspect, concerning tents, they more than make up for with their knowledge of sails.

The intense thunderstorms of last night grudgingly dissipated by morning so the plan to climb Europe Peak and walk the Continental Divide to Hay Pass seemed like it might be possible. However, the air remained heavy with moisture and by the time I gained the 250 m to Europe Pass, the clouds were moving in. With some misgivings, I continued up the increasingly intricate route along the divide and after an hour, reached the summit and a good 360° view. What was becoming obvious over the past hour was now undeniable. Walking along the talus-strewn exposed 8 km ridge today would probably be risky and committing, with no quick way off the broad flat expanse. I believe there is more danger in being terrified of lightning than actually being struck by it, having seen bruises, cuts, broken bones and a death due to panic rather than electrocution. However, there's nothing like a bit of static electricity in the air to prompt a quick attitude adjustment. With sprinkles here and there, the descent from the summit required a bit of attention, being rocky and somewhat exposed in sections. But just as I reached the pass, the sun broke out again. In my experience, morning thunderstorms are rarely harbingers of pleasant afternoons so I returned to my camp, still some 250m below. The further I descended, the bigger the sucker holes became and by the time I reached camp, the skies had taken on a begnign summery appearance. Screw you nature. I had resigned myself to resuming the Wilson-Dixon route. I packed up, made a short descent down-canyon and turned north, soon reaching Long Lake and the intricate, cliff-filled passage along its east shore where, like one of Pavlov's dogs, I now reflexively chose the higher route, eventually rounding the head of the lake and the shallow pass marking the head of the North Fork of Boulder Creek. The water here flows along a broad, nearly flat glacial valley in a northerly direction past Glacier Lake (of course) and toward the base of Hay Pass before dog-legging abruptly back south through the North Fork Canyon on its journey to join the Green. By the time I reached the dog leg, the day was ending and the final decision was that of picking a campsite among dozens. There was no decision to be made on dinner. It was an Ichiban evening. The stuff has roughly the same caloric content as a serving of freeze dried food and weighs in at a mere 100 grams. Some butter, onion flakes and a dash or two of habañero sauce adds some character. Best of all, it is cheap, helping to defray the exhorbitant cost of my nascent romance with the ultralight. Somewhere on the site there is an equipment list.

The country below and to the south of Hay Pass has seen the hooves of countless sheep and cattle as well as a skirmish or two between respective barons. One leg of the enabling legislation for the USDA includes grazing so the "Land of Many Uses" continues to endorse it as traditional use. Conflicts between sheep and cattle have been replaced with conflicts between sheep and backpackers, but in recent years those too have become less common. Herders in the Winds now ostensibly have been educated to exhibit more discretion and public awareness in their activites. There is some effort made to soften the impact of this multiple use through scheduling and locating grazing allotments where the people aren't. If history teaches us anything we choose not to ignore, it is that things rarely change much, but I believe that in the case of grazing, likely because of the economic advantages of feed lots and superfarms - as well as public pressure, the presense of sheep and cattle has become a bit more of a curiosity than a certainty.

Hay Pass sneaks up on you, and you're not quite sure you've arrived until it becomes apparent that you're headed downhill toward Dennis Lake which eventually, and quite unexpectedly comes into view. I prefer studying maps after a trip rather than before, and in the case of the Winds, where navigation in clear weather with just a simple compass bearing is straightforward, letting the next turn in the path provide some anticipation. For the same reason, my inReach® remains tucked away until an emergency or the end of the day (whichever comes first). Happy to be descending rather than climbing the path, it is a matter of minutes to the Golden Lakes Basin where a left turn takes you up the drainage past three delightful lakes and a remote chance of seeing members of your species fishing the long-ago stocked lakes. Though a trail up Bull Lake Creek leads to the basin from the east, it is next to forever to the trailhead. Upon arriving at Upper Golden Lake, the highest lake in the basin, I once again left the Wilson-Dixon route leading to the Alpine Lakes basin and instead, headed west cross-country up a drainage toward another crossing of the continental divide. I passed a couple of lakes that had, at sometime in the past been stocked for fish were rising to feed on a hatch that was taking place. Eventually I reached the top of a promontory overlooking a rocky basin with some small tarns. I would have to descend 50 meters os so from here in order to continue up to the divide. I couldn't see anything in the surrounding area that might make a better camp than where I was standing, it was getting on into late afternoon and it would take me a full two hours to go up and over the divide, then descend to somewhere suitable for a camp. The possibility of afternoon showers and a desire to spend some time on the divide made this seem as good a spot as any to stop for the day. There was a level patch of sedge between two large rocks and a pond nearby. That sealed the deal. I set up my tent thinking that my freeze-dried Chicken Tetrachloride would taste pretty good tonight.

"Stable and dry" in Pinedale does not mean stable and dry at 3200 meters in the Winds. A "chance of afternoon thundershowers" there translated to "rain" and my camp was no exception. While I never got wet while walking, evenings in my tent were a different matter. Half the nights of my 10-day trip included rain and/or snow, and it gradually cooled during the period, so it was no surprise to find verglas on the rocks this morning on the way up to my fourth and final crossing of the Continental Divide. This crossing was in the most delightfully obscure country yet. The only nearby name on the map was "Tiny Glacier", which ,upon closer inspection could only be more sympathetically named "Extremely Tiny Glacier". With a heavy heart for the thing and it's struggle to survive - anthropomorphism has no bounds when you have been alone for a week - I headed down to Wall Lake. There were fish rising and I thought about stopping here but it would make for a long day tomorrow to Peak Lake, so I climbed north out of the drainage and found a place to camp on the hill overlooking Island Lake. Just right.

My hope to sneak around Island Lake unnoticed was dashed with the appearance of two young women in running tights and sports bras. They stopped and asked for directions to Indian Pass. After 8 days of isolation, this encounter was disarming, though they seemed not to notice what I hoped were polite stares. Wondering if this was somehow part of a grand plan, I mumbled something about taking the next right. They were off at a joggers pace with a fleeting glimpse of athletic buttocks and fettered breasts. I considered all the possible, less-desirable alternatives to this encounter and concluded that after eight days of solitude, my resocialization could have been much worse. I was 20 minutes or so up the Titcomb Basin trail when the two reappeared. They had missed the turnoff to Indian Pass, it was beginning to drizzle, and they had only light windbreakers. It turns out they were speed hikers and asked if I had seen a couple of girls who apparently were their SAG team. I said no and suggested that they might have taken the path that they had missed. One produced a cell phone - from where I do not know - and after a couple of tries, realized there was no signal. Both were starting to shiver. A brief discussion between them made it apparent that they intended to take the Indian Pass trail and catch up with the others. I regretted my previous comment, picturing them freezing high in the basin while their companions sat in camp. I had a brief image of three people in a one-person tent, struggling to survive hypothermia, then sensibly suggested that they hightail it back to their camp and wait for better afternoon weather. I got a strange look from one as the other revealed that they had come from the trailhead that morning! As they dissapeared toward the lake and I continued up the trail, my steps were a little lighter and Knapsack Col didn't seem so far away. The women reminded me that, at 78, I was not dead yet. Perhaps tomorrow, but not today.

The approach to Knapsack Col and the subsequent exit along the Green River drainage stretches all the way up Titcomb Basin to the base of Bonney Pass before turning abruptly west for the final 500m ascent along the moraine of the Twins Glacier. At 3736m this is the highest point on a route that, from day one, never drops below 3000m It fittingly yields the most spectacular view and at times, the only real dicey ground of the walk. Upon reaching the col, the pesky ceiling lifted to reveal the varigated west walls of Mt. Helen, Mt. Sacegewea, and Fremont peak, inspiring the requisite feeling of utter insignificance for any trip worthy of inclusion in the "Totally Awesome" category. Dutifully humbled, cold and hungry, I took a few "sad you're not here" photos and began the long, meandering descent to Peak Lake and my final camp. There were great campsites just above the lake with afternoon sun and killer views. I chose a spot within earshot of the fledgling Green River and settled in. I dozed like a lizard until the sun left. I congratulated myself for cleverly camping near the water, filled everything, ate dinner and promptly passed out for the night.

Things would have remained perfect had it not been for an overnight rain-turning-to-snow storm and the persistent shade cast by Sulpher Peak on what I now realized was an idiotic location for a campsite. It would be hours before the sun reached my camp so I schlepped my wet gear and frozen single-walled tent 100m to sunshine. This resulted in a gentleman's start to a 30km day, and aside from the obvious climbs over Cube Rock and Vista Passes, the appearance of the remainder being all downhill to the trailhead was fantasy: according to gps data from the web, there lurked nearly 700m total ascent when the relentless ups and downs were tallied. The two passes accounted for just a bit more than 400m. During the nearly 12-hour walk to the trailhead, I met only 6 people coming in, all below Three Forks Park and well into the afternoon. If I walked out at the same pace that they walked in, it was going to be a death march to the truck. The afternoon wore on onto evening and each little uphill into and out of the forest along the lakeshores became longer and higher than the last. I now realized with each little hill where all that extra elevation gain was coming from. I foolishly made, then regretted a quick and dirty calculation that I would have to cover another 8 km to account for the elevation gain remaining. I could hear my always-jovial Italian friend with his happy pronouncements of "only 300 meters to go Jim!, only 280 meters to go Jim..." The evil reality is that there is precious little level walking along the two lakes, and they are big lakes. In the darkness between the lakes, I thought I saw a cat in my headlamp, but it was late and if it wanted to eat me, ok. I reached the trailhead at about 11 pm after almost as many hours of walking. After 10 days on foot, 40 miles-per-hour seemed like an insane speed but it worked out. Three hours later and two narrow-misses with elk on the roads, I was home - eating ice cream ...

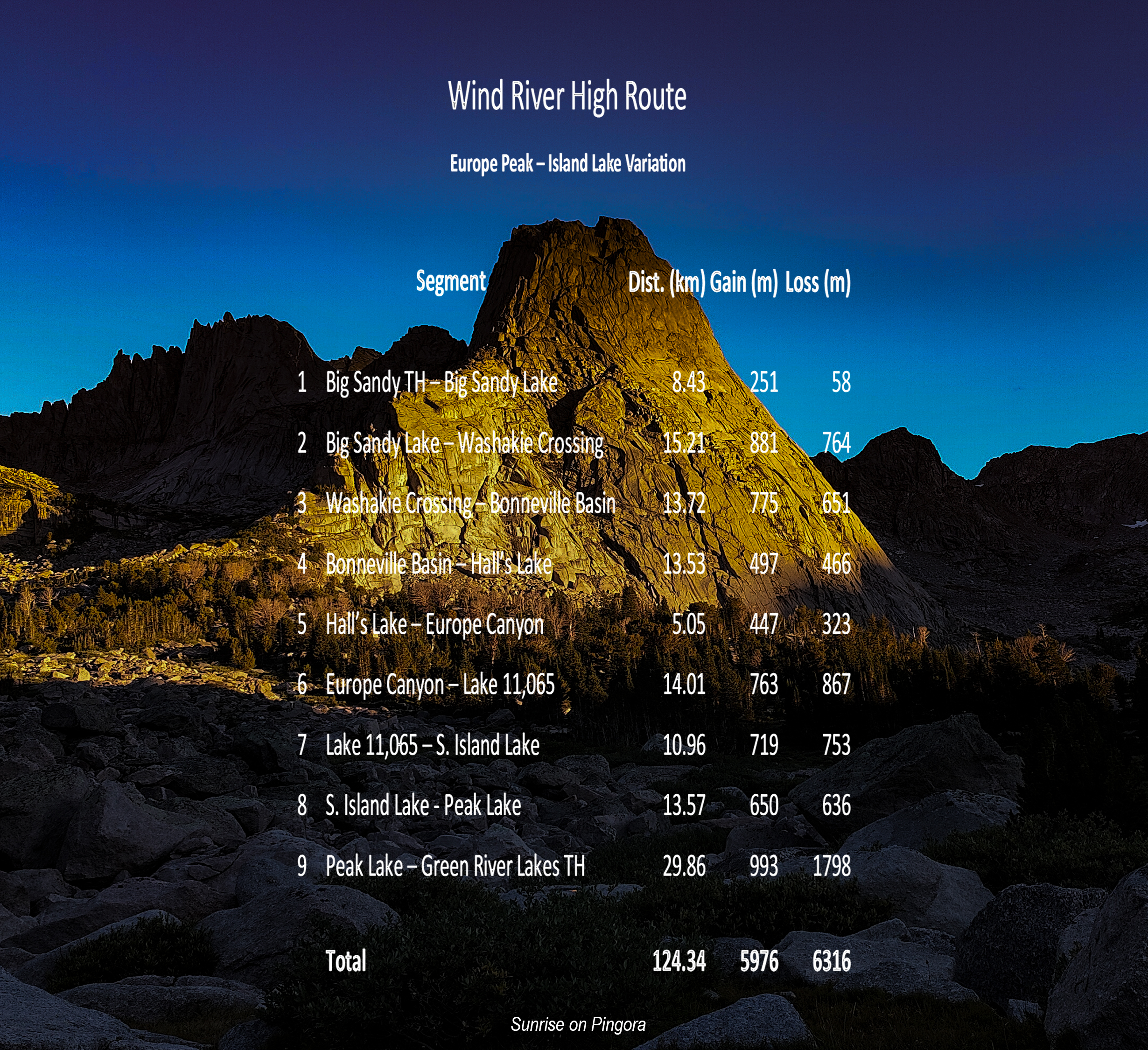

The first question that people ask about this walk is how it compares to other "thru-hikes" that I have done. There is no comparison. There are no huts, or refuges with warm beds, hot food and cold beer. There are no towns or cable-cars or trail angels. There were, in this case, no people over a week's time - an increasingly rare circumstance. There is now a faint trail (in some places requiring imagination) however, to be found along the standard segments of the route that link both the mapped trails with a large number of use trails established since the last USGS survey. After ten years of its introduction to the internet, I suppose that is to be expected. I picked up a candy bar wrapper on a strech of marked trail and saw evidence of one campsite a mile south of Island Lake. Given the popularity (or at least publicity) the route has gained, I expected to see someone between the Cirque of the Towers and Island Lake but I was pleasantly disappointed. So the answer really depends upon what you're looking for. My pack weighed 9.8 kilos dry of which 3.6 kilos was food. I also carried an InReach, a cell phone (there is coverage here and there) and a 10 watt flat solar panel with a 3200 mAH battery. Those items brought the total up to 11.1 kilos. There was no shortage of water. The temperatures during this mid-September period ranged from 78° to 21°. There were four thundershowers and two overnight storms that left ice on (and in) my single walled tent. The last left a muddy trail and two inches of snow in the shady areas near Cube Rock Pass on the last day, the 15th of September. See the track information for distances and elevation. Happy trails.

"Don't go too fast, but I go pretty far ..."

- Melanie Safka -

![]() will do just what it says and take you down another rabbit hole.

will do just what it says and take you down another rabbit hole.